June 2, 2013

Texas

I’m writing this on a return trip from Dallas and Marfa, Texas, where I was part of a series of performances of Gerard Grisey’s percussion sextet, “Le Noir de l’étoile”, organized by the Yellow Barn Chamber Music Festival based in Putney, Vermont.

This is a work I now have a firm understanding of and relationship with, having given five public performances and two school programs, four of which occurred over just this past week. For these most recent performances I had the good fortune of joining an incredible cast of colleagues: Eduardo Leandro, Douglas Perkins, Ian Rosenbaum, Timothy Feeny and Ayano Kataoka, as well as Jeff Lowes, our audio engineer who ran the PA system and made sure we all sounded our best.

Eduardo Leandro, Doug Perkins, Ian Rosenbaum,

Greg Beyer, Ayano Kataoka, Tim Feeney.

After two beautiful performances at the astonishingly gorgeous Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas this past Wednesday, we traveled to the remote western Texas town of Marfa to give two more performances over two nights on the property of Ranch 2810, some six miles outside of the town of Marfa heading southwest.

The second performance was absolutely remarkable, but I’ll get to that shortly.

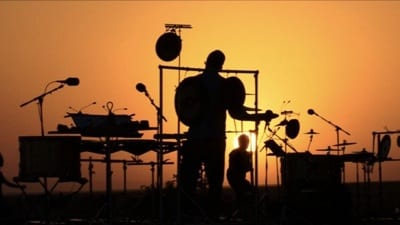

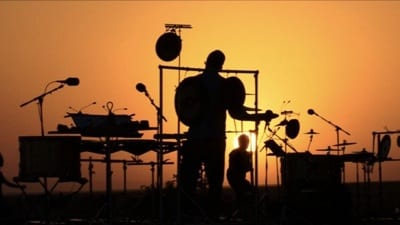

On our first evening, we arrived in the late afternoon to set up our percussion gear on the platforms laid out that morning by Eduardo Leandro and Roland Musquiz, accompanied by Roland’s son, Ramon. (Roland and Ramon provided most all of the instruments and the platforms themselves and drove well over ten hours each way between Dallas and Marfa to accommodate this endeavor!) The western wind was high and the afternoon sun was ablaze but its dramatic light provided incredible vistas in all directions. And, as the sun gradually set over the western horizon, spilling vivid blue and indigo over a landscape that was only minutes ago lit up gold and auburn, the wind predictably set alongside it. Evening calm.

platform – before and after

Our lead percussionist, Eduardo Leandro, along with Yellow Barn’s Artistic Director, Seth Knopp, and its Executive Director, Catherine Stephan, had come out to Marfa last November specifically to determine the perfect time and location for this past week’s events. They succeeded. As we finished our prep work, the desert the sun set, the temperature became perfectly cool, the wind died, the air became peaceful, and on that moonless evening, the stars became incredibly bright and vibrant in the desert sky. For a piece about the life and death of stars, a more perfect scenario is simply unimaginable. I believe Grisey himself would have been ecstatic.

* * *

Our audience the first evening consisted of students and their teachers and parents from the Marfa International School, a new, innovative and progressive school for grades 1 through 8. Marfa is unique – it seems to have a strangely bifurcated double passport to accommodate its dual citizenship/citizenry. Its inhabitants include multiple generations of Mexican Americans whose homes, neighborhoods and lifestyles are outwardly modest. Their homes, churches and other buildings are constructed low to the ground in earthen colors that blend easily into the surroundings. By contrast and literally on the other side of the railroad tracks, Marfa plays (oftentimes second or third) home to an extremely wealthy artistic community, largely inspired by its “founding father” Donald Judd. Judd’s untitled minimalist cubes in both concrete (outside) and milled aluminum (inside) grace the campus of the Chinati Foundation (formerly an army barracks known as Camp Marfa and Fort D. A. Russell). While the concrete creations form something of a line along the eastern edge of Chinati’s grounds, two inline former military truck garages (and one-time German prisoner of war camps in the 1940’s), house Judd’s aluminum collection. These two buildings are elegantly retrofitted with quonset-hut style rounded corrugated steel roofs (to keep the rain out, I was told) and beautiful large panes of glass that look over that eastern portion of the campus grounds in which Judd’s collection of concrete blocks reside. Inside the pair of buildings, three rows of aluminum boxes installed equidistantly on the floors account for a collection of 100 variations on a minimalist theme. Each box at first glance seemed nearly identical but, after time and careful observation, the subtle details and differences between each iteration became sharply clear.

I fell in love with one box in particular which caught my eye because of the manner in which the mid-afternoon sunlight poured through its “box-inside-a-box” design. Sitting cross-legged in front of it, I gazed through its various openings to see distant cars passing, blue-bellied lizards frolicking immediately outside the window pane and, in mid-distance, Judd’s concrete cousins sitting stoicly on the arid desert campus.

sitting with Donald Judd

An upbeat young intern, Katie, showed me through the collection of Dan Flavin’s fluorescent-light installations for the Marfa campus, housed in six adjacent U-shaped dormitory style buildings. I found that I enjoyed this installation most not as I approached the cool electric lights but as I turned and walked away from them, moving instead towards the pair of windows on the opposite end of each hallway. These windows opened back onto the arid campus and Judd’s concrete blocks. I found that the natural light they spilled into the room seemed to me a deep breath of fresh air after the immersive experience of the fluorescent tubes and their quiet but incessant 60-cycle hum. In the work of Dan Flavin I found and appreciated deeply the tension and release of moving to and from synthetic and natural light.

* * *

Back at the Ranch 2810, our first evening’s performance was preceded by a “percussive petting zoo” which proved to be (as it always does) an easy hit and a chance to meet and talk a bit with our audience members, young and old alike.The calm night offered up the possibility for another audience altogether, lured to our stations not by our musical offering but by the LED light spilling from our music stands and mallet trays. Moths, crickets and still other insects appeased their curiosity on the pages of my music and the surfaces of my drums and cymbals. One slightly more aggressive spirit made its way to my right arm and gave me a good little pinch when I tried to whisk it away. Once playing began, however, the evening ensued calmly, peacefully, strangely quietly despite the occasional passagework of incredibly loud music that Grisey composed in “Le Noir.” The performance was both solid and pleasing. The audience of not more than 50 people listened attentively and clapped politely as we finished the 70 minute work under an incredible canopy of stars. The sky was so clear that the Milky Way was easily apparent – its hazy lace draped behind the myriad constellations and planets much closer to home.

* * *

What made our second night’s performance so incredible was Mother Nature’s voice and visceral presence throughout the evening. When we arrived at the ranch at 5:30PM to ready our stations, the wind was already quite high. Moreover, it was coming in from the east – the front of a storm was making itself known to us miles ahead of any visible storm clouds. We instinctively knew this to be a very different wind from that of the previous evening.

the storm cloud approaches from the east

As we prepared for soundcheck the sun continued to beat down and the wind did not abate. The Paiste “rotosound”, a disc of smooth bronze affixed atop a long metal rod with a spinning joint that allows the metal to rotate rapidly when struck, is used for the final moment of the piece. It was positioned atop a cymbal stand at the center of our hexagonal pinwheel set-up. And in this night’s strong air current it became a rudderless weathervane, whipping silently, rapidly around and around without any human provocation. So inspired, as the sun began its descent just above the horizon, it too became a blinding disc of white hot metal.

the sun turned a white hot metal

The minutes quickly passed and the wind only grew stronger. A large and rapidly approaching storm cloud now appeared in the eastern sky. It rode its windy chariot ever closer but, to our relief, its direction broke and it continued to the south. Nonetheless, its drama carried on in the form of distant bolts of lightning, briefly illuminating the southern sky. The wind grew stronger still.

We retired to the back porch of 2810‘s beautiful ranch home to rest before the concert, clean the dust off ourselves and change into our concert attire. At the point when we decided to head to our stations once again, the eastern wind met our western approach with menacing force. I watched from the opposite edge of the hexagon as the gong and tam tams in my set-up laughed clangorously in the wind. Suddenly, the largest tam could no longer keep its grip on its stand and took flight directly into my set of roto-toms. Doug Perkins let me borrow some tie line and scissors to harness the instruments. En route to my station, I stopped to assist Ian Rosenbaum with his tam tam as well. As I approached my set I found that I was late on arrival. Just ten paces in front of me the tam tam came crashing down onto the platform a second time.

The wind blew harder still.

Roland Musquiz was on hand to assist with the job of tightening down the stand. Catherine Stephan and Matthew Shetrone, a kindly astronomer from the McDonald Observatory just outside of nearby Fort Davis, also appeared. Collectively, we tied back not only the tam tam and gong but the rack itself – battening its hatches and tethering it firmly to the underside of my station’s platform. For extra security, I took down the smaller tam tam which was suspended on high from a cymbal stand. It was simply not going to last through what was becoming a ferocious wind. The scene made it seem as if the platform had literally become a meager raft in a wild and tempestuous sea. After what seemed like eternal prepping to “set sail”, Catherine and Seth Knopp moved to the center space and addressed the audience. My colleagues and I stepped inside our set-ups. The performance would soon be underway.

The wind, a Southern gentleman, momentarily calmed itself as Catherine spoke. However, after Seth concluded his forward and the voice of Grisey’s French narrator began, all Southern hospitality was dismissed. Although tightly tethered, the metal discs on the rack behind me were now nipping at my back under the wind’s fury. I stepped back off the platform and found Roland.

“Would you mind holding my rack steady?”

He gladly came over and climbed onto the back of the raft.

The wind whipped up even more strongly as Eduardo Leandro began playing the first notes of the piece. Shortly thereafter his first page turn became a 15-second struggle as Catherine and another member of the audience jumped up to assist. They would find themselves negotiating Edu’s page turns under the wicked wind for the next hour.

As I watched my cymbals cockeye grotesquely at all angles under the blowing wind, nervous adrenalin filled my veins as I waited my turn to enter the cycle.

“Deux,” announced the same French narrator, this time only into the privacy of our in-ear monitor system, letting the six of us know that we’d reached rehearsal two. Doug entered with his first notes, barely audible under the whipping wind whistling its own music loud and clear into all of our microphones and threatening to drown out that of M. Grisey. Our sound engineer, Jeff Lowes, masterfully negotiated this “musical dialog” to avoid feedback and sonic disaster during our performance.

I glanced back at Roland. Good. His grip was firmly secured to the tam rack.

“Cinq.”

Ian entered the fray.

“Six.”

I took a deep breath in, then slowly exhaled.

“Sept.” (click-click-click)

…and I’m in…

music firmly secured with clips and stones

The moment of my first note instantly transformed my state of awareness. With the wind whipping at my back my nerves calmed and I focused acutely on the music in front of me. “I’m flying,” I thought. It really felt like how I imagine flying to be, too, with the wind beneath both mental and musical wings.

I was now inside Grisey’s musical vortex and there was no looking back. Each burst I delivered on my set of wooden planks was met in kind with powerful responses from my colleagues, first Ian and Doug to my right, then Tim and Ayano in rapid succession off to my left.

Our unison moment at rehearsal 14 was blazingly brilliant. We soon passed from the creeping drum passages at 24 and ascended toward the powerful snare drum entrances at 27. I turned my torso to the left to deliver the first of a series of sforzississimo attacks on my large tam tam…knowing that its voice would be a poor substitute for the small tam tam that I had taken down because it threatened to fly into the audience. As I turned, I was therefore surprised to see something totally unexpected. I gave out an uncontrollable bit of delighted laughter…there was Roland, holding up the top of the cymbal stand that held my small tam tam, now flying high like a proud flag hoisted over my paltry vessel. To meet his gesture, I happily laid into each note and every note. I couldn’t believe it. Roland knew my part well enough to do that for me. We were now co-captains on this ship sailing over the roiling waves. Onward!

We reached rehearsal 40, my long gong attacks and rolls as magic carpet rides for the superball glisses and fingertip smears of my colleagues. I play the first roll. To my dismay but in retrospect not at all to my surprise, the instrument rattled against the ropes we used to keep it from flying away in the wind storm. I wound up to play the second roll…Roland’s hand suddenly appeared from out of the darkness, adroitly widening the space between the rope strands just wide enough to allow the instrument to sing freely.

Roland Musquiz. After all of the toil and all of the trouble, he proved to be the true Southern gentleman of the evening.

“Cinquante six!”

the “vela” pulsar

We reached the first pulsar recording, the “Vela” pulsar, the final clatter of mallets on our wooden boards bleeding into the Vela’s pyrotechnic sputtering like a mad drum-and-bass groove. I turned around and gave Roland a little head rub from over the gong rack.

“Thank you!” I whispered. He gestured a fist bump and I turned back around to prep for the second section of the piece.

* * *

Over the course of the remaining 40 minutes of music the wind continued to blow but gradually slackened its intensity. The piece accordingly became more focused and more enjoyable to play. And each time I turned to play the tam tams, Roland hoisted our “mast” back up on high. Brilliant.

We reach the final page turn.

“Cent quarant et un!”

Now on the home stretch, our rapid fire 16th notes are careening in every direction around the ensemble.

“Cent cinquante!”

I play my final bar of music, turn off the snares.

“Cent cinquante un!”

One by one I turn off my stand lights, turn around and exit my platform.

“Cent cinquante deux!”

Heading right, I reach my mallet tray, turn off the stand light then quickly proceed around the back to the opposite corner of the station.

“Cent cinquante trois!”

Grab chime mallet and flashlight…

“deux…”

Turn off the final LED, stand tall.

“trois…”

Steady my balance, then purposefully walk forward toward the center of the audience…

“quatre…”

Seth illuminates the rotosound disc as I approach…

“cinq…”

Right hand turns off the flashlight, tosses it on the ground, arriving at the foot of the rotosound…

“Cent cinquante quatre…deux, trois, quatre, cinq, six!”

Arm high, hammer swing, metal blow, recede into darkness…

…back at my station I watched on as Seth slowly, artfully covered the flashlight, one finger at a time, then plunged the world into darkness.

The only light remaining became the unspeakably beautiful canopy of stars over the West Texas desert. Two hundred and fifty people sat quietly, gazing up into the stars with only the accompanying hum of a disk of metal, struck just minutes ago and still spinning in the now gentle breeze.

All this, a small human-sized homage to the miracle of intercepted radio waves emitted from stars that died thousands upon thousands of years ago.

* * *

twilight at Ranch 2810